‘…profound changes are impending in the ancient craft of the Beautiful…’

When Walter Benjamin decided to start his now-famous essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, with these words from Paul Valéry, his attitude towards the future they envisioned might be described as ambivalent at best. Writing in 1936, in the early years of what would become the golden age of film, Benjamin, like Valéry, recognized the potential for technology to bring the beauty of art to ever-widening audiences. At the same time, he could also foresee the ways in which these same advancements might threaten the very essence of artistic tradition and experience — namely, by chipping away at the uniqueness and material presence of previously hand-crafted, aesthetic objects, and in doing so dampening what he dubbed their ‘aura’.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Benjaminian aura lately, partly because I’m in the middle of writing an essay about the experience of presence at theatre broadcasts, and partly because I spent the last two weeks of my research trip in the US looking at the ghostly side of technology. Benjamin understood aura as emanating from the unmediated, a-technological artefact — ‘that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art’ — but the more I look at digitally rich productions of Shakespeare and their historical precursors, the more I find myself thinking about the auratic or spectral potential of technology itself. Take, for instance, the production still above, which comes from a 1913 book about Hamlet based on Jonston Forbes-Robertson’s silent film of the same year. This book, held in the Folger Shakespeare Library’s collections, uses images from the film to illustrate a prose version of Shakespeare’s tragedy. What struck me most as I perused its pages were the photographs featuring the ghost of Hamlet’s father, who takes the shape of a bright, ethereal spirit produced by innovations in film technology. To see how the ghost flickers in and out of frame in the movie, have a look at the clip below.

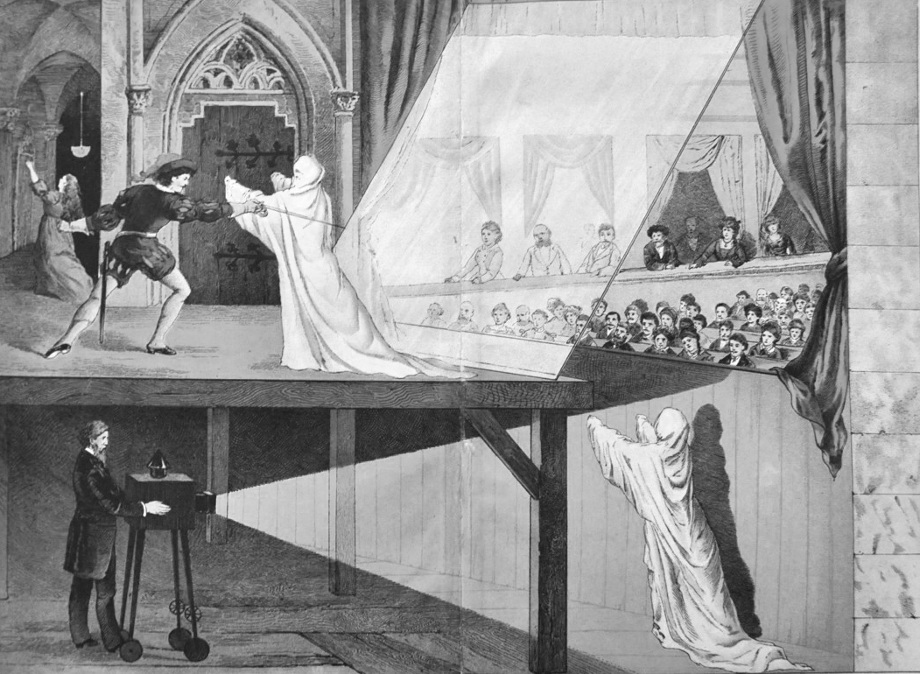

The creative use of technology in the performance of Shakespeare is not unique to film, particularly when it comes to staging the supernatural. John Gielgud’s 1964 production of Hamlet on Broadway, starring Richard Burton, featured an audio recording of Old Hamlet’s lines recited by Gielgud himself, accompanied by a looming shadow on the wall, to body forth the ghostly presence of the late king. Long before that, John Pepper created a similarly ethereal ghost of King Hamlet in the nineteenth century by using mirror and light technologies to project the reflection of an actor onto the action of the stage (see the image below for an illustration of this technique, known as ‘Pepper’s Ghost’). In both cases, ingenious uses of technology allowed theatre-makers to present a disembodied version of King Hamlet’s ‘aura’, or, to quote from the Oxford English Dictionary, that ‘subtle emanation … viewed by mystics as consisting of the essence of the individual, serving as the medium for the operation of mesmeric and similar influences’.

Even beyond the obviously supernatural figure of the ghost, I’ve increasingly found that Hamlet stands out in the archives as one of the most frequent plays that actors and directors look to when they want to explore what technology might tell us about Shakespeare. Some of the productions I’ve been reading about lately include Robert Wilson’s staging of Heiner Müller’s Hamletmachine (1986), Robert Lepage’s one-man show Elsinore (1995), the Wooster Group’s reconstruction of Gielgud and Burton’s Hamlet (2006), Katie Mitchell’s multimedia exploration of Ophelia in Five Truths (2011) and Ophelias Zimmer (2016), and finally Annie Dorsen’s ‘machine-made’, algorithm-based version of the play, A Piece of Work (2013).

While all of these productions use technology in different ways, I find it interesting that Hamlet repeatedly proves fertile ground for mechanical, multimedial, and digital experimentation. Perhaps this is due to the sheer fame and monumentality of the play, but I also wonder if there’s something particularly haunted and haunting about Hamlet that continually seems ripe for technological exploration. There is of course the play’s obsession with death and all the ‘things in heaven and earth’ that push beyond the limits of our philosophy, as well as the tragedy’s own gargantuan and even superhuman literary and theatre history, which looms so large in the study and performance of Shakespeare. Shakespeare himself has often been memorialized by lines from Hamlet — ‘He was a man, take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again’ — and perhaps, in a way, all of us who are drawn to Shakespeare’s work find ourselves obsessed and even haunted by Hamlet for at least a time.

Indeed, the more I think about it, the more it seems like Hamlet is a play that started out being about death but that has become one of resurrection. It’s not just that it shows us a young man facing the spirit of his dead father — though that of course is significant. It’s also that in its virtually unparalleled cultural legacy, it connects us with a never-ending history of scholars, actors, directors, critics, and thinkers of all kinds who have come before us and pondered this seemingly insurmountable testament to human creativity. When we look on Hamlet, we also look on those who have been there before us. Their ghosts are with us alongside the Old King’s.

Maybe the next thing, then, for theatre-makers to experiment with are hyper-real technologies such as 3-D holograms that have started to appear on other stages in recent years. At Coachella in 2012 the long-deceased rapper Tupac Shakur astonished audiences when he appeared to take the stage alongside Dr Dre. Imagine Laurence Olivier coming back to give his final turn as Old Hamlet, or Richard Burton, or even Shakespeare himself, given that he too is sometimes said to have played the role. It’s possible that such innovations, with their complicated ethics, are a bridge too far. But even if this is the case, I have no doubt that directors and actors will continue to mine new technologies to bring us freshly startling takes on the ghost of Hamlet’s father, and, indeed, on the tragedy of Hamlet itself.