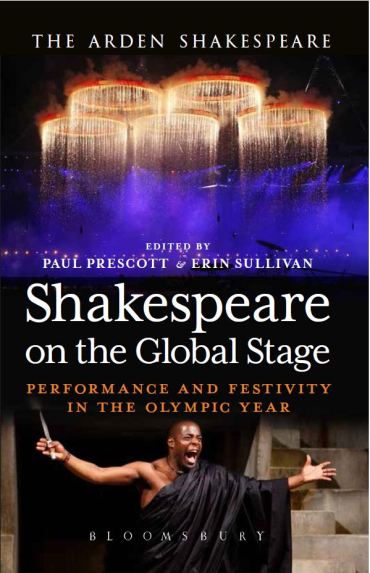

Busy but exciting times — some of you know that for the past several years I’ve been working on a project exploring Shakespeare’s presence in the 2012 London Olympics. At the end of January, the final installment of this research was published, in the form of a beautiful and thought-provoking collection of essays from Arden/Bloomsbury entitled Shakespeare on the Global Stage: Performance and Festivity in the Olympic Year. Below are a few Olympic Shakespeare-themed tweets I posted in celebration of its launch, as well as an excerpt from the book’s preface giving a list of its contributors and the questions and arguments they explore in their chapters.

Speeches from Shakespeare were recited in 3 of the 4 London 2012 @Olympics and @Paralympic ceremonies #olympicshax http://t.co/vW3HCpcLp3

— Erin Sullivan (@_erinsullivan_) January 20, 2015

The 2012 #culturalolympiad included c.75 productions of Shax, over 50% in languages other than English #olympicshax http://t.co/vW3HCpcLp3

— Erin Sullivan (@_erinsullivan_) January 20, 2015

Olympics literature cites Shakespeare’s *King John* as origin of the phrase ‘fair play’ #olympicshax — Erin Sullivan (@_erinsullivan_) January 21, 2015

From the Preface…

In the autumn of 2011, the Royal Shakespeare Company announced its plans for ‘the greatest celebration of Shakespeare the world has ever seen’. The RSC’s World Shakespeare Festival (as it came to be known) would form a major part of the London 2012 Cultural Olympiad, and would feature such highlights as the Globe to Globe Festival at Shakespeare’s Globe. Together these projects would bring dozens of Shakespearean productions from overseas to British stages, as well as inspire a range of new interpretations by UK companies. Anticipating what was an unprecedented and possibly unrepeatable moment, a group of UK-based scholars created an informal collective with the expressed aim of documenting and debating the performances of Shakespeare in the Olympic year. Reviewers were dispatched to the nearly seventy productions, and their responses were promptly posted on the project’s website, www.yearofshakespeare.com. A few months later, these pieces would be published together as A Year of Shakespeare: Re-living the World Shakespeare Festival (Arden, 2013).

If that book reflected the ‘documentation’ of the Festival, offering short, eye-witness accounts of what it was like to be caught up in the celebrations in ‘real time’, this book makes space for the longer view, inviting authors from the UK but also abroad to pursue the range of complex issues raised by the collocation of the Olympics and what we call ‘Shakespeare’. One of the paradoxes of mega-events like the Olympics is that while the event is intensively concentrated in the host city and nation, it is nevertheless designed for the enjoyment and consumption of a truly global audience. In calling this book Shakespeare on the Global Stage, we try to capture the sheer reach of the internationally visible outcomes of the 2012 Olympics, but this book is also profoundly interested in the build-up and backstage histories that lie behind that final spectacle.

Paul Prescott begins by exploring the overlaps between the philosophy of Olympism and the various forms of dream work performed by Shakespeare in 2012. The juxtaposition of two previously unpublished poems by Kapka Kassabova – a writer in residence in Stratford-on-Avon in the Olympic year – invites the reader to consider the relationship between a captured moment of parochial festivity and the weight and responsibilities of global citizenship. Interviews with Frank Cottrell Boyce, Tom Bird and Tracy Irish offer reflective and personal accounts about the process of scripting, producing and teaching Shakespeare for and on the global stage.

The next two chapters consider the politics of culture from the perspective of nation and region, analysing the relations between space, identity and representation. Stuart Hampton-Reeves focuses on the interrogation of nationhood offered by three Globe to Globe productions; he uses this so-called Balkan trilogy to reflect on boundaries and faultlines within London in the lead-up to the Olympics. Adam Hansen and Monika Smialkowska question the boundaries between local, national and global, and tease out the ways in which the northeast of England was and was not represented in the 2012 festivities.

The Globe to Globe Festival shifted our understanding of the nature of cross-cultural exchange between performer and audience. Stephen Purcell and Rose Elfman’s chapters draw on both quantitative and subjective accounts of spectatorship to explore the ways in which audiences collaborated in the creation of meaning and value throughout the Olympiad. The networks of global production behind the World Shakespeare Festival are interrogated by Colette Gordon in her analysis of the sometimes problematic ways in which one continent – Africa – signified and was represented across Olympiad programming.

The following two chapters offer telling comparisons, one synchronic, the other diachronic. Peter Kirwan and Charlotte Mathieson’s chapter analyses the ways in which London (and other spaces, real and virtual) celebrated and remembered two canonical writers, Shakespeare and Dickens (2012 was the two hundredth anniversary of the novelist’s birth). Tony Howard finds echoes in 2012 of the last London Olympics of 1948, in which international cultural exchange benefited the British understanding of Shakespeare in another age of austerity. The promise of far-reaching legacy underwrites every Olympics, and Erin Sullivan’s concluding chapter considers how investment in Shakespeare in 2012 connected with an optimistic, if unrealized, vision of Britain’s global future. Finally, in her afterword Kathleen McLuskie weighs the virtues of that optimism against the almost intractable complexity of capital and culture, reflecting on the irreconcilable pressures and pleasures that Shakespeare celebration in the Olympic year exerted on the individual.