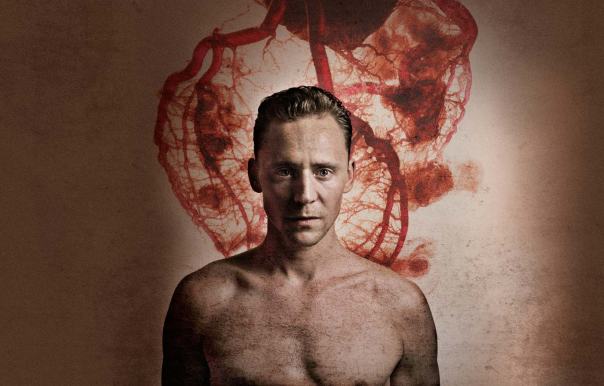

Like thousands of other people across the UK, in January I made my way to my local cinema to see Tom Hiddlest— er, Coriolanus, broadcast live from the Donmar Warehouse to the silver screen. The Donmar is a small theatre – 251 seats, according to my A4 programme – so it’s not unusual for it to sell out, but it doesn’t usually do so so quickly, and so entirely, as it did for this Shakespearean production. I knew going into the show that people liked Tom Hiddleston, apparently dubbed ‘the sexiest man on the planet’ by MTV (as we were reminded in the interval programming), but I didn’t know quite how much. I was lucky to see him live in 2006 in Cheek by Jowl’s The Changeling, and then again the following year as both Posthumus and Cloten in their Cymbeline, before his star ascended and tickets to his productions turned almost literally into gold dust. He was excellent in both shows, and in particular Cymbeline, where he had more to do and his doubling of the male leads added to the surreal, maze-like quality of that strangely charming play (not to mention that he made Cloten a lot more attractive than is usually the case).

This time around, Hiddleston was undoubtedly the main draw, and again he made a typically taciturn character – Caius Martius, later Coriolanus – into a suppler, more emotionally rich figure than we have perhaps come to expect. For me that interiority was achieved against the grain and even in spite of Shakespeare’s text, the result being that Hiddleston’s supremely watchable and even enthralling performance could never be a definitive Coriolanus for me – not enough sneering violence, not enough sociopathy. He was still great, though, and I’d love to see him as a Brutus, or even a Hamlet, in the years to come.

For someone interested in the relationship between the filmed and stage version of this production, Hiddleston’s involvement provided an interesting test case. His celebrity itself blurs the boundaries of theatre and film, encouraging audiences from one realm to enjoy the delights of the other. More than a few newspaper reviews of the production noted the youthfulness of its audience, the implication being that this Coriolanus helped generate interest both in Shakespeare and in theatre among groups more typically drawn to blockbuster cinema – and if that is true, then all the better. On a much more practical note, though, Hiddleston being in this show meant that there was no way in hell I was going to get a ticket to it, and that I was one among many in such a situation. Live broadcasting to cinemas becomes all the more pertinent in such circumstances. With demand far exceeding supply, new possibilities for access to the production meet a clear and demonstrable need. My cinema in Stratford-upon-Avon was filled to the brim, with at least two ‘encore’ screenings to follow, and I wouldn’t be surprised at all if most other cinemas broadcasting it across the country were met with a similarly fulsome crowd.

The remarkable demand for tickets for this production, however, means that any discussion for me of the broadcast itself must be limited to that – the broadcast alone. And it was an interesting one. To date all of the broadcasts and live filmings that I’ve seen of Shakespearean productions have been from relatively large, spacious stages, often with a very strong sense of place: the Globe in London (Henry IV parts 1 and 2, Globe to Globe), the RSC mainstage in Stratford-upon-Avon (Richard II), the amphitheatric Olivier at the National (Othello), a highly atmospheric, reclaimed church in Manchester (Macbeth). The Donmar, with its intimate scale and spare black-box of a stage, is a markedly different kind of space, and not one that necessarily lends itself to visual tableaus or epic camera sweeps. What would the screened experience be like?

The first indication we got of an answer came in the form of an overt Brechtianism that was starkly distinctive from the more pictorial setting evoked at the start of the RSC’s Richard II in November. Young Martius ran on with a paintbrush splashed with red and swiftly drew a large square outline around the stage-space, a bloody chalk circle of sorts. Inside was a single vertical ladder, behind a set of empty chairs and Roman graffiti projected on the back wall. But while these physical features may have gestured towards a Brechtian theatre of alienation, or even the German playwright’s own staunchly socialist reworking of the play in the 1950s (retitled Coriolan), neither possibility evolved into something more significant once the production really got going.

Instead, in the play’s opening scene we encountered a chaotic, disjointed mob, angry in their demands and reckless in their threats. The camera moved rapidly, coming at the actors from all three sides of the Donmar stage, with the swift and sometimes dramatic cuts between different angles adding to a sense of frantic divisibility. This was in no way the ordered, noble citizenry assembled at the start of Brecht’s play, but rather a disgruntled fringe spurred on by a particularly aggressive First Citizen, whose longer speeches were cut (‘We are accounted poor citizens…’, ‘If the wars eat us not up, they will…’) and whose belligerent, bullying lines were accentuated (‘Let us kill him!’, ‘He did it to please his MOTHER!’). Very little camera time was offered to either Citizen Two or Three, and once Menenius/Mark Gatiss/Mycroft entered the stage the focus turned resolutely to him and his mincingly triumphant, if heavily curtailed, belly fable.

Until, that is, Caius Martius/Tom Hiddleston came into the scene – and all the cuts to the preceding action meant that his entrance occurred easily within the first ten minutes of the show, perhaps even the first five. With the camera fixed on him, and the three citizens positioned at separate corners of the square stage, Martius was alpha dog to their skittish, ineffective pack – the un-unified, undignified ‘fragments’ he imagines them to be. When he scornfully announced that they would be granted tribunes to represent them, they whooped and hollered on stage, but to no clear political end. The victory seemed to be more in winning itself than in the gain of any real power or authority.

In terms of the filmic style, the chief visual mode for this production was no doubt the close-up, and what’s more the close-up from many angles. I counted upwards of 42 changes in the sequence that leads to Martius’ banishment, which probably occurred over roughly 80 lines in performance. This meant that we were averaging close to one camera shot per 1-2 lines, the result being a very directed point of view.

Not long after attending this broadcast I watched an extended interview with the British director Steve McQueen, known for his use of resolutely, even unsettlingly, long takes in his films. In response to a question about a 17-and-a-half-minute long shot in his 2008 film Hunger, which features a dense and fiery conversation between the IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands and a priest, McQueen described the long shot, especially when it contains multiple characters, as one that demands a different kind of watching from its audiences. While conversations divided into close-ups project the location or meeting point of the conversation into the audience itself, the long, sustained, and wider shot requires the audience to project themselves into the scene, to acknowledge themselves as spectators and voyeurs and to make sense of that experience.

In a way McQueen seems to be saying that in film the long shot is more radical and involving because it observes what we might call the fourth wall, while the broken up, sequenced shot is less so because it directs the story straight into the world of the audience member, obscuring any sense of theatrical divide. This seems somewhat at odds with how theatre historians and performance critics often understand the observation or ‘breaking’ of the fourth wall, but I suppose in a cinematic broadcast we are dealing with two frames of reference – the theatrical one and the cinematic one – and that we are in turn navigating a potentially double divide. What is the result?

Well, the honest answer is that I still don’t entirely know, but my sense is that many theatrical broadcasts are dealing with it by trying to jump over and beyond it. This Coriolanus was very intimate, even claustrophobic – though to be fair, the Donmar as a space is too, so wide or distant perspectives simply aren’t a part of the theatrical experience it offers. One thing that struck me throughout the broadcast was how so many of the full-stage shots came from either above or below eye-level, almost as if the camera had to back into the upper and lower crevices of the space in order to squeeze in the wider view. And while many shots tracked with the actors, few if any tracked through them – that is, moved through the stage space even if the actors themselves were more or less stationary (something I found especially compelling in the Richard II broadcast). Occasionally, we were treated to a level and fairly open view of the stage from one of the downstage corners, which for me were the most effective shots. With them I felt that I had a perspective that offered a fuller understanding of the theatrical space and the actors within it, without feeling so cramped or craned.

But for the most part, the multi-angle close-up predominated, offering an emotional intimacy and naturalism that highlighted what seemed to me to be an especially and even excessively emotional Coriolanus. It was certainly unBrechtian in this regard – the constant approach was that of empathy, identification, interiority, with Coriolanus himself very much the victim and very little the enemy of the people. Haughty, yes, but more foolhardy than anything else. Tears were in abundance, and the camera worked hard to highlight them as much as possible – in the first domestic scene, close ups on Virgilia’s silent tears worked to sculpt a greater sense of character out of what is ultimately a very tiny part, and in the closing sequence Coriolanus’s own steady tears became the chief visual motif running through the supplications of his wife, child, friend, and mother.

Perhaps it was the Coriolanus that this space, and this actor, demanded – in the interviews preceding the broadcast, Josie Rourke described the Donmar as ‘a deeply psychological space that has to be enormously truthful’, and for me Hiddleston’s very moving, very ‘truthful’ Coriolanus was most absorbing even when he was most outside what I think the part actually demands. It’s understandable, then, that the camera work in this broadcast sought to capture and even heighten these strengths, but I still couldn’t shake the feeling that I wanted the visual frame to slow down, and to back off. I wanted to see and explore more of the stage space on my own terms, to attend to Hiddleston’s powerful presence and even celebrity within the context of the whole theatre (audience included). I wanted the visual narrative to breathe. But maybe that’s not how this production worked, irrespective of the screen.

4 thoughts on “Stage, space, and celebrity: Coriolanus at the Donmar”